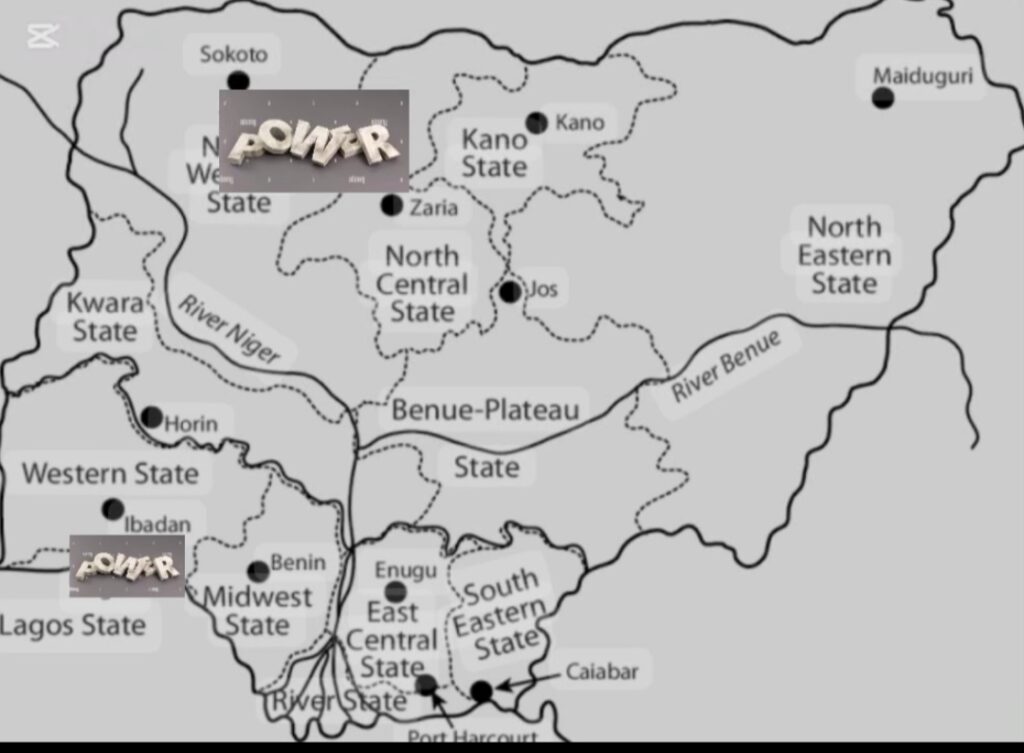

Since the annulment of the June 12, 1993, presidential election—widely believed to have been won by Chief MKO Abiola—Nigeria has been trapped in a cycle of power rotation that favors two regions: the South West and the North West. The past three decades of leadership transitions, often dictated by political maneuvering rather than national interest, have ensured that these two regions maintain a firm grip on the presidency. The question remains: has this power structure benefitted ordinary Nigerians?

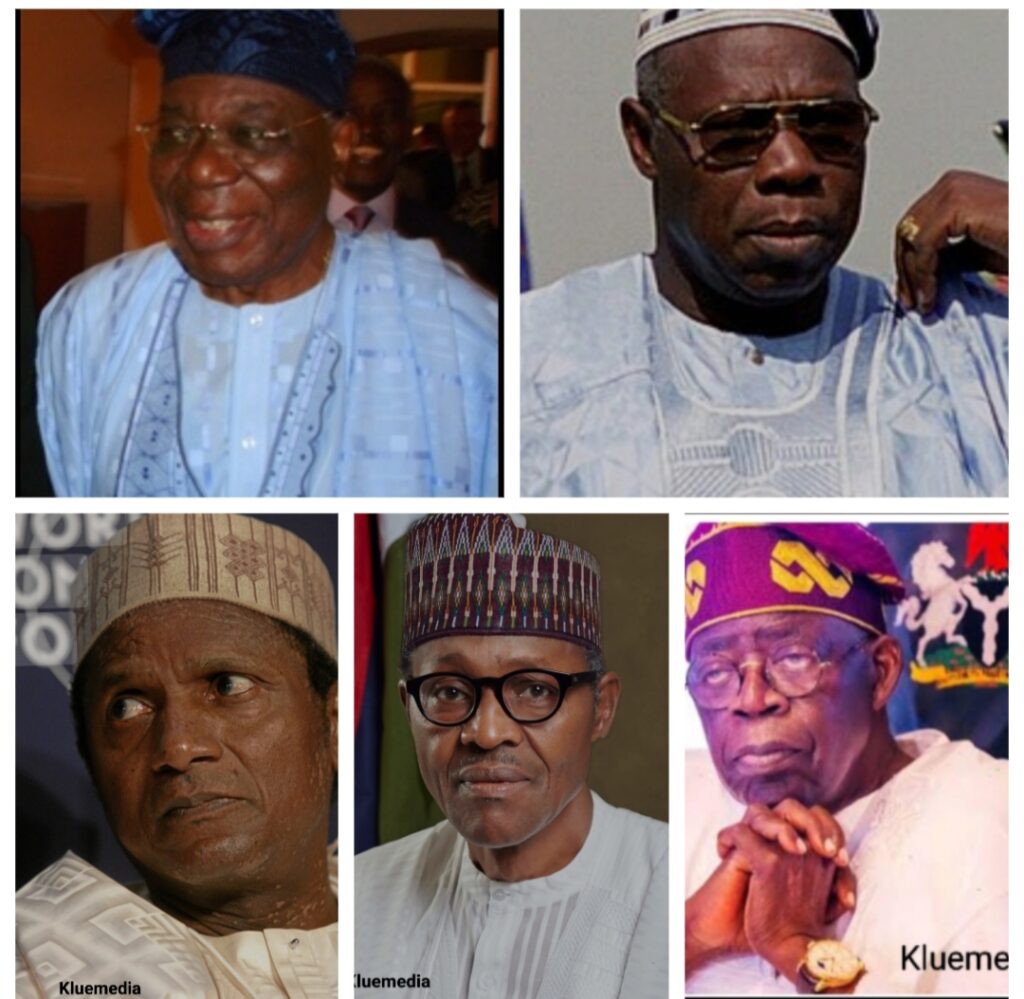

Following the annulment of June 12 Presidential election, General Ibrahim Babangida (IBB) installed an interim national government (ING) led by Chief Ernest Shonekan, a South Western corporate executive. But the ING was doomed from the start. On November 11, 1993, Justice Dolapo Akinsanya ruled the arrangement illegal, citing that IBB had already resigned before appointing Shonekan. Despite the legal battles, what stood out was the fact that Babangida had left the military under the direct control of General Sani Abacha, a setup that many believed was a calculated move.

Barely six days after the court declaration, on November 17, Abacha staged a bloodless coup, ousting Shonekan. Born to Kanuri parents but raised in Kano, Abacha functioned politically as a North Westerner. His reign was characterized by a desperate ambition to rule indefinitely, much like Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe and Cuba’s Fidel Castro. However, fate had other plans he passed suddenly on June 8, 1998, at the age of 54. His passing was soon followed by the controversial passing of Chief MKO Abiola, the man many Nigerians still recognize as the rightful winner of the 1993 elections.

With Abacha gone, the country needed stability. Enter Chief Olusegun Obasanjo, a South Western former military head of state, who was ushered in as Nigeria’s next civilian president in 1999. His administration focused largely on economic reforms, but his greatest political miscalculation was his attempt to amend the constitution to extend his tenure beyond the mandated eight years. The North, determined to resist, blocked the move. Obasanjo had no choice but to step down in 2007, handing over power to a North Westerner, Umaru Yar’Adua, a man whose leadership is still nostalgically remembered for its sincerity and vision. Unfortunately, his time was cut short by illness, and he passed in office in 2010.

In Yar’Adua’s absence, power shifted, for the first time in Nigeria’s history, to the Niger Delta region. Goodluck Jonathan, an Ijaw from oil-rich Bayelsa State, rose to the presidency, not by design, but by circumstance. His journey from deputy governor to president was marked by political serendipity: first, his principal was impeached, elevating him to governor; then, his boss died, making him president. But Jonathan’s tenure faced an unusual level of hostility, particularly from the same political forces that are in power today, Muhammadu Buhari and Bola Ahmed Tinubu.

The opposition to Jonathan was relentless. His economic policies, particularly his efforts to shift Nigeria away from an unsustainable consumption model, were sabotaged at every turn. The West, both the South West and the North West, wanted him out, and so did the United States under Barack Obama. Western powers, wary of Nigeria’s rising economic independence, saw an opportunity for regime change. In what now appears to be a carefully orchestrated political coup, Jonathan was replaced by Buhari in 2015.

Buhari’s presidency marked the return of North Western dominance, but more importantly, it paved the way for the grand objective: the emergence of Bola Ahmed Tinubu, the South West’s most formidable political tactician. The South West had backed Buhari with one goal in mind—to secure the presidency for one of their own. And in 2023, that goal was realized.

This cycle of South West and North West leadership has persisted since IBB’s handover to Shonekan. The only times it was interrupted were when a leader died (Yar’Adua) or when a transitional government was required (Abdulsalami Abubakar’s administration in 1998–99). But beyond the politics of power rotation, the pressing question is: has this leadership structure improved the lives of Nigerians?

Despite the decades of South West North West leadership dominance, Nigeria has become one of the poorest nations in the world, with citizens relying heavily on foreign aid. The presidency, rather than serving as a vehicle for national transformation, has become a prize that rotates between the same power blocs while the rest of the country suffers.

Nigeria needs a true structural shift, one that prioritizes national development over regional dominance. Leadership must be inclusive, and governance must serve the people, not the interests of a select few. The current system has failed to deliver prosperity, and unless intentional and drastic changes are made, the cycle of economic decline and political stagnation will continue.

Nigerians must wake up to the reality that power rotation between two regions will never bring national progress. It is time to dismantle this unproductive arrangement and build a leadership framework that reflects the true diversity and needs of the country. Anything short of this will only keep us trapped in an endless loop of recycled leadership and wasted potential.

Odey Otunu.